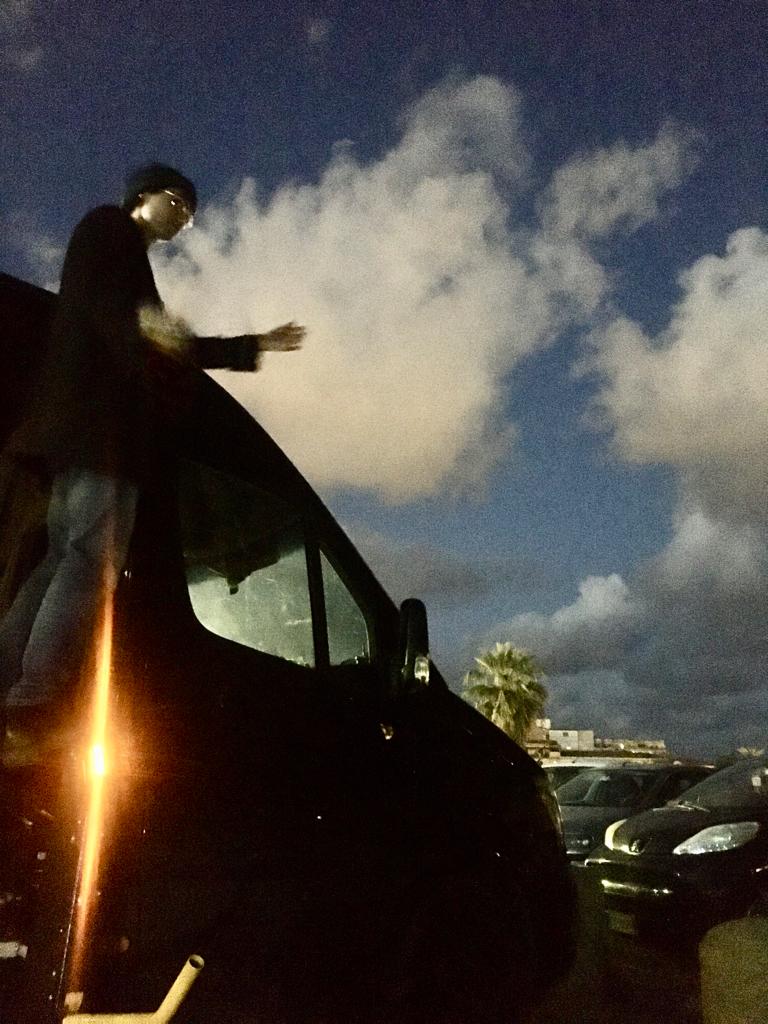

Auf ihrer aktuellen Tour durch Europa trat Pussy Riot am 15.05.2022 auch in St. Johann in Tirol auf. Das Kulturzentrum Alte Gerberei war bei dieser einzigen Show in Österreich ausverkauft.

Die Aktivist*innen und Künstler*innen Maria („Masha“) Alyokhina, Diana Burkot, Olga Borisova und Anton Ponomarev standen gemeinsam mit ihrer multimedialen Performance im Zeichen der Solidarität mit der Ukraine auf der Bühne. Die Erlöse der Tour und des Verkaufs von T-Shirts und Büchern wird an ein ukrainisches Krankenhaus gespendet.

Die gleichnahmige Performance basiert auf Alyokhinas Buch Riot Days und behandelt Pussy Riots Aktivismus gegen Putin und sein Regime seit Anfang 2012. Die russischen Lyrics, in Untertiteln übersetzt, wurden von thematisch passende Videoclips auf der Leinwand begleitet. So wurden beispielsweise Szenen des Punk Prayers von 2012, des darauffolgenden Prozesses oder von Aufständen gegen Putin, in den Saal gebracht, was dem Publikum dementsprechend tief unter die Haut ging.

Die letzten Aufschreie der Performance galten explizit dem Krieg in der Ukraine. In blutrotes Licht getaucht sangen die Aktivist*innen zu Sirenentönen (übersetzte) Parolen wie „Putin likes your indifference / West was selling him wapons for 10 years“ oder „Mama I’m held in captivity / Don’t watch the TV / Mama there are no Nazis here / Mama, why the war / Is called a ,special operation’?“. Der Beat war eingängig, doch mit „Buchaaa“-Aufschreien und begleitenden Videos wurden ich und viele Zuseher:innen um mich herum mit einer gefesselten Sprachlosigkeit zurückgelassen.

Im Anschluss an die Performance nahm sich die Pussy Riot Aktivistin, Sängerin und Texterin von Riot Days, Olga Borisova Zeit für ein ausführliches Interviewgespräch, das als spontane Kooperation zwischen Mar_ry von das mensch.gender_queer on air und dem Studierendenmagazin Die Zeitlos entstand. Das folgende Interview ist in englischer Originalsprache in gekürzter Fassung wiedergegeben. Der Link zu Mar_rys Radiosendung ist hier online verfügbar.

Die Zeitlos: Hi Olga, thank you for taking the time to talk to us! Since when do you identify yourself as a member of Pussy Riot?

Olga Borisova: I think since 2015 or 2016, because then we started to do the book and that’s a Pussy Riot project. After we finished the book, we started to do political actions together. So, if we talk about actions of Pussy Riot,my first action was around 2016, I think.

That’s a long time…. On a very basic level of emotions, are you ever afraid when doing actions?

There were moments when I was super afraid. For example, when we did an action in Crimea. Then I got detained basically every time I was leaving any building. We were detained a lot and then police took all our devices. They stole my phone, too, because I was calling my lawyer. They said: “You have no right to call a lawyer or even to use your phone.” And I was like “Why? Why are you here though? I’m doing nothing.” Basically, they were just afraid that we’d do action in the Crimea – which was actually our plan, but yeah…

So when we arrived at the police station, we found our devices, but they were broken. Not visually, outside there were no changes, but we couldn’t turn them on. What they had done is that they put twelve volts inside. So, my new iPhone was burned out and we couldn’t use or even fix it even more.

That was scary because without any connection to media or a lawyer, you’re a nobody, you can disappear. So that was, I think, the scariest moment when we’re talking about police.

But apart from that, I don’t know. Especially now when it’s war… I mean, I left Russia when the war started… So now I live in Georgia. It’s an amazing country, and it’s a victim of the Russian regime as well, because 20 percent of Georgian territory is occupied by Russia. Actually, [in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Anm.] it’s a very similar story to the Dener and Elener, which is Luhansk national Republic and Donezk national Republic.

Now a lot of independent journalists from Russia live there because it’s easier for us, there we don’t need visa there for one year. So, they’re all either in Lithuania or in Georgia. Now I left Georgia, but still… Russia can open a criminal case against me, for example because, I talk about sanctions a lot, and how West should be more brutal about sanctions towards Russia. We also have a criminal article against people who are asking for sanctions against Russia. Everything can happen… But now in Georgia I kind of feel safe because they’re, you know, they are very radical about the Russian regime and Putin. Now when it’s a war, I think it’s not, it’s not scary because the least we can do is tell the truth.

How is Pussy Riot perceived in Russia? Can people even know about you?

Well, they know about it because of Russian propaganda. They covered the whole trial [regarding “Punk Prayer” in 2012, Anm.] and used it. A lot of people think that it was girls who were naked in church. Even my boyfriend used to think that and he’s Georgian.

A lot of people think that they [Pussy Riot, Anm.] hate Christianity for example. Most Russians think that way because they consume the propaganda and we don’t have like [free, Anm.] TV – all TV channels are pro-Putin. We don’t have any criticism of Putin or Russian government in the media.

So, the majority of people, they don’t know about independent media, for example, or they are too busy trying to survive because we have 20 million people living in poverty.

So, they can’t afford to think about that…

Yes exactly, they just… they are working hard to just provide for their families. So, they don’t have time to think about anything else – the regime for example. But this regime is basically the reason why they are poor: Because Putin stole all natural resources that are supposed to be owned by all people that live in Russia.

That’s why Pussy Riot has this reputation, but in my circles, like defendants, journalists, activists – people that care about politics, they are fans of ours.

Maybe on a more positive side, can you tell us about what gives you hope?

That’s a very popular question but it’s also an interesting question. I experienced a terrible emotional burnout as an activist. Because you do something – for example, you’re trying to save some political prisoners and you talk about them – but nothing will happen… Nothing happens after that. So, when you’re an activist, it’s crucial to first think of your mental health. If you can’t save yourself, if you’re not stable, you can’t help other people. So, this is about some work-life balance.

But about hope – uhm, I don’t know, just thinking… I’m just thinking that it’s the right thing to talk about that and it’s not right to be silent.

So, you don’t really think about hope. As an activist, especially in Russia, you wouldn’t do anything if you think about the results and the outcome. Of course, if you go out on the street and protest, you’ll be detained and then nothing will happen. The war won’t stop. But you just feel this urge to do something. So that’s the motivation – and you can’t do otherwise. We performed in Berlin, in Funkhaus, which is a radio station. It was a complex of different buildings that was owned by communists, and it was the main buildings of Soviet propaganda in Eastern Germany. And now it’s an amazing spot for techno raves and for concerts and for orchestras. Actually this gave me some hope because I was like: “Okay, that was the main propaganda, Soviet propaganda in Germany. And now people have fun here and they use this space for fun, for art – this is amazing.”

So, this gives hope and kind of brings some ideas what we could do with KGB (laughs) in Russia, which is now FSB… But yeah, we have a lot of buildings… Like the parliament because we basically don’t have a parliament, it’s all pro-Putin. We don’t have any anti-Putin politician or people in charge… That’s not possible because we don’t have real elections. We have elections, but basically Russia is half a dictatorship because Russia is still pretending to keep democratic procedures, but they are faking it.

But this gives hope because it was like this before [in Berlin, Anm.] and you can see how it changed. So we just, I don’t know… We just need to be louder and work on it. And also, about politicians – I don’t see any hope in our politicians. I’m more like an anarchist, myself. So, I’ve never was excited about the politicians, but I see how the West just completely ignored all of them… – not even Russians speakers, but human rights activists everywhere, from post-Soviet countries, but Russia is now a super aggressor that… This is why Finland is now planning to attend NATO. (laughes) Finland, that’s crazy!

And Sweden too, actually…

Crazy – Sweden and NATO…. But, and it’s also maybe not good though, but this is how they rag because they need to protect themselves. So, they need to, it’s two sides and they don’t really have a choice. So, I see how western countries completely ignored what we all said, you know, other political figures, human rights activists, that actually had many meetings with American figures and Western, European figures, European leaders and they’d be like: (sarcastic voice) “Yeah, yeah, we support you. Uh, yes, Putin is bad. We will do a visa for you. Thank you so much. Let’s do a picture for Twitter. We are good, we supported them, we payed for their hotel in our town. So yes – bye!” (laughes)

And then there is a war. After the annexation of Crimea, we see nothing had happened, because they did some nominal sanctions, but it wasn’t effective. And the guy, Putin, understood that. There’s no basic responsibility, there is no hard consequences. So, he can manage … and he can start a war. Now, finally West is awaken. Not completely, but now we have like very crucial sanctions.

But also, I don’t think it’s a very good idea of me as an anarchist to hope for some Western losers. (laughes)

And now these West figures are thinking like “Why, Russia, just won’t vote against him.” It’s delusional, you know? But it’s not right time to talk about Russia, I think. Russia is an aggressor and that also is the whole narrative. Basically, because we don’t have democracy there, because Putin is doing what he’s doing we have war in Ukraine. But now, of course, I think the focus should be on Ukrainian people and their suffering.

Thank you so much for taking the time and talking to us!

Nach dem Gespräch mit Olga Borisova war mein Kopf übervoll mit Gedanken und mein Herz mit Emotionen. Der Kontrast der lauten und intensiven Performance zuvor und dem späteren, nicht weniger intensiven, aber ruhigeren Gespräch war stark und doch griff beides ineinander. Ich war und bin voller Ehrfurcht vor Olga Borisova, Pussy Riot und all den anderen Aktivist*innen, die trotz Verfolgung und Strafen gegen das Regime kämpfen. Es ist so vieles, was ich aus diesem Treffen mitnehme, was mich weiterhin beschäftigt und doch ist es ein Satz, der sinngemäß aus Performance und Gespräch hervorstach, der mir beim Nachhause gehen immer und immer wieder durch den Kopf geht:

„Freedom doesn’t exist unless you fight for it every day.“

Beitragsbild: Berit Neumayr